Section 2.4 Three Dimensional Coordinate Systems

Key Questions

At the end of this chapter you should be able to answer these questions.

- What is a right-hand Cartesian coordinate system?

- What are direction cosine angles and why are they always less than 180°?

- How are spherical coordinates different than cylindrical coordinates?

In this section we will discuss four ways to specify points and vectors in three-dimensional space,

- Rectangular (Cartesian) Coordinates

- Direction Cosines

- Spherical Coordinates

- Cylindrical Coordinates.

You will often need to convert from one representation to another, and good visualization skills will be helpful here.

Subsection 2.4.1 Rectangular Coordinates

We can extend the two-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system into three dimensions easily by adding a \(z\) axis perpendicular to the two-dimensional cartesian plane. The notation is similar the notation used for two-dimensional vectors. Points and forces are expressed as ordered triples of rectangular coordinates following the same notation used previously.

Alternately, points and vectors in three dimensions can be expressed in terms of direction cosines, or with spherical or cylindrical coordinates and these will be discussed in the following sections.

For nearly all three-dimensional problems, you will need the rectangular \(x\text{,}\) \(y\text{,}\) and \(z\) components of each vector before proceeding with the computations. If you are given the components upfront, then you are set to move forward, but otherwise you will need to be able to transform one coordinate system into rectangular coordinates.

Thinking Deeper: Right Handed Coordinate Systems.

Does it matter which way the axes are oriented? Is it ok to make the \(x\) axis point left or the \(y\) axis point down?

In one sense, it doesn't matter at all. The positive directions of the coordinate axes are arbitrary. On the other hand, it's convenient for every one if we can agree on a standard orientation. In mathematics and engineering the default is to orient the coordinate axes with the right hand rule. Coordinate systems which follow this rule are right-handed.

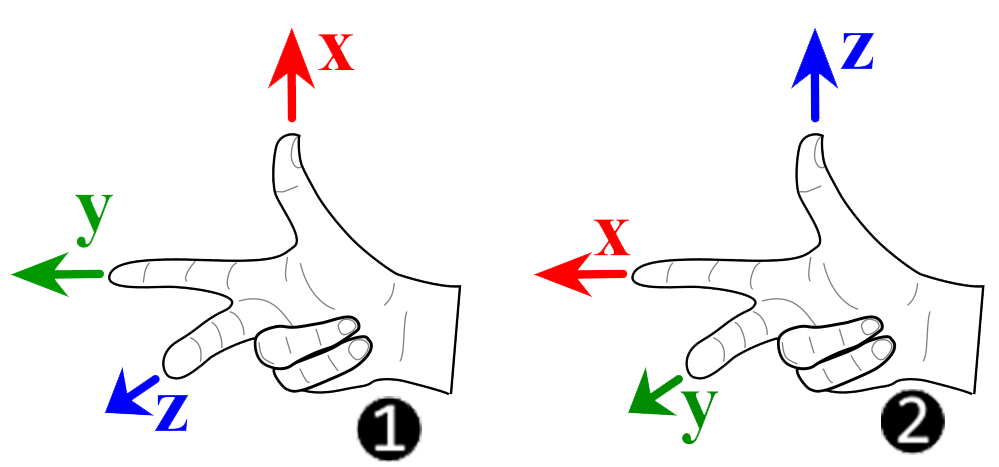

To apply the right hand rule, orient your thumb and first two fingers at right angles to each other and align them with the three coordinate axes. Starting with your thumb, name your fingers in alphabetical order \(x\)-\(y\)-\(z\) as in diagram ❶.

These are the labels for the three axes and your fingers point in their positive directions.

If it is more convenient, you may name your thumb \(y\) or \(z\text{,}\) as long as you name the other two fingers in the same sequence \(y\)-\(z\)-\(x\) or \(z\)-\(x\)-\(y\text{.}\)

Subsection 2.4.2 Direction Cosine Angles

The direction of a vector in two-dimensional systems could be expressed clearly with a single angle measured from a reference axis, but adding an additional dimension means that one angle is not enough to specify the direction of a vector.

One way to define the direction of a three-dimensional vector is by using direction cosine angles, also commonly known as coordinate direction angles. The direction cosine angles are the angles between the positive \(x\text{,}\) \(y\text{,}\) and \(z\) axes to a given vector and are traditionally named \(\theta_x\text{,}\) \(\theta_y\text{,}\) and \(\theta_z\text{.}\) Three dimensional vectors, components, and angle are often difficult to visualize because they do not commonly lie in the Cartesian planes.

We can relate the components of a vector to its direction cosine angles using the following equations.

Note the component in the numerator of each direction cosine equation is positive or negative as defined by the coordinate system, and the vector magnitude in the denominator is always positive. From these equations, we can conclude that:

- Direction cosines are signed value between -1 and 1.

- Direction cosine angles must always be between \(\ang{0}\) and \(\ang{180}\) or\begin{equation*} \ang{0} \le \theta_n \le \ang{180}. \end{equation*}

- Any direction cosine angle greater than \(\ang{90}\) indicates a negative component along that respective axis. Spatially this is because all direction cosine angles are measured from the positive side of each axis. Mathematically this is because the cosine of any angle less than \(\ang{90}\) is numerically negative.

Subsection 2.4.3 Spherical Coordinates

In spherical coordinates, points are specified with these three coordinates.

- \(r\text{,}\) the distance from the origin to the tip of the vector,

- \(\theta\text{,}\) the angle, measured counterclockwise from the positive \(x\) axis to the projection of the vector onto the \(xy\) plane, and

- \(\phi\text{,}\) the polar angle from the \(z\) axis to the vector.

Question 2.4.2.

What the differences between polar coordinates and terrestrial latitude/longitude locations?

In terrestrial measurements

- Coordinate \(r\) is not needed since all points are on the surface of the globe.

- Latitude is measured \(\ang{0}\) to \(\ang{180}\) East or West of the prime meridian, rather than \(\ang{0}\) to \(\ang{360}\) counterclockwise from the \(x\) axis.

- Longitude is measured \(\ang{0}\) to \(\ang{180}\) North or South of the equator, where as polar angle \(\phi\) is \(\ang{0}\) to \(\ang{180}\) measured from the “North Pole”.

Vectors are specified similarly in cylindrical coordinates, except that the magnitude of the vector is used instead of distance \(r\text{.}\)

When the two given spherical angles are defined the manner shown here, the rectangular components of the vector \(\vec{A} = (A\; ; \theta\; ; \phi) \) are found thus:

Reflect on the equations above. Can you think through the process of how they were derived? The generalized steps are as follows.

Draw an accurate sketch of the given information in either orthographic or isometric view and define the right triangles related to both \(\theta\) and \(\phi\text{.}\)

-

Use trig identities on the right triangle involving the vector, the \(z\) axis and angle \(\phi\) to find

the component of \(\vec{A}\) adjacent to \(\phi\text{,}\) and

the projection of \(\vec{A}\) onto the \(xy\) plane.

Use trig identities on the right triangle involving vector \(\vec{A}'\) and \(\theta\) to find the remaining components of \(\vec{A}\text{.}\)

Subsection 2.4.4 Cylindrical Coordinates

Cylindrical coordinate system are seldom used in statics, however they are useful in certain geometries. Cylindrical coordinates extend two-dimensional polar coordinates by adding a \(z\) coordinate indicating the distance above or below the \(xy\) plane.

Therefore cylindrical coordinates, points are specified with these three coordinates.

- \(r\text{,}\) the distance from the origin to the projection of the tip of the vector onto the \(xy\) plane,

- \(\theta\text{,}\) the angle, measured counterclockwise from the positive \(x\) axis to the projection of the vector onto the \(xy\) plane, and

- \(z\text{,}\) the vertical height of the vector tip.

Subsection 2.4.5 exercises

Unfortunately, not all problems give the angles \(\theta\) and \(\phi\) as defined here here; so you will need to know how to derive equations for the given angles in any problem.

You can use the interactive diagram in this section to practice visualizing and finding the components of a vector from a given magnitude and polar angles \(\theta\) and \(\phi\text{.}\) You should be able to find the \(x\text{,}\) \(y\text{,}\) and \(z\) coordinates given direction angles or spherical coordinates, and vise-versa.